Enhance your health with free online physiotherapy exercise lessons and videos about various disease and health condition

Osteitis Pubis

Osteitis pubis in athletes is also known as 'pubic symphysitis' and 'traumatic osteitis pubis', and sometimes comes under the broader discussion of 'footballer's groin'.

It (or pubic symphysitis) is believed to be a self limiting disease of the symphysis pubis, marked by erosion of either one or both of the joint margins, followed by a process of healing. The disease affects men more frequently than women (at a ratio of about 5 males to 1 female among athletes) and presents in athletes in their twenties and thirties.

History of pubic symphysitis

Osteitis pubis has been discussed in the literature since 1924, when E. Beer described a periostitis of the symphysis and descending rami of the pubis following suprapubic operation. However, in 1923, Legeu and Rochet had described 'osteite pubienne' and as long ago as 1827 Elliotson reported in the London Medical Gazette a case of prevesical abscess in a female in which the pubis was rough and blackened and denuded of its periosteum, but not carious.

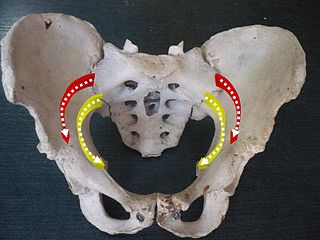

Historically, the literature from the early 1920's until the mid 1950's discussed osteitis pubis as a problem of pelvic infection together with a range of vascular factors, problems of pregnancy and localized reflex sympathetic dystrophy all perhaps contributing from time to time.In 1953 however, Adams and Chandler suggested that direct or indirect trauma to the symphysis could produce an osteitis.It was proposed that perhaps the pull of the rectus abdominis muscles could initiate the problem and further work went on to examine the role of the muscles involved in running and kicking. Notably, the adductor muscles were cited as the key factors in producing shear forces across the symphysis, leading to instability of the joint.While adductor pull on the symphysis was being considered, Williams (in the UK) was examining the role of limitation of hip joint movement as a factor in osteitis pubis in athletes. Williams noted an association between the loss of internal rotation of the hip and the finding of tilt deformity of the head of the femur, which had been noted in active adolescent athletic males.He went on to propose that sporting activities such as soccer and road (race) walking require free internal rotation of the hip joint in both flexion and extension. If such movement is restricted, stress is applied across the hip joint to the hemipelvis on the opposite side. This produces shear, which results in inward or outward movement (anteroposterior) of one half of the pelvis in relation to the other in extension, or upward and downward movement (proximodistal) in flexion. In addition to these factors, it should be remembered that conditions which limit movement at one pelvic joint (such as the sacroiliac joint) may induce stress at other pelvic joints. The spondyloarthropathies (including ankylosing spondylitis) may thus come under suspicion. Such conditions typically affect young men and may in fact present as a periostitis of the symphysis pubis, rather than the more characteristic sacroiliitis.

Osteitis pubis in female athletes

In female athletes this condition does seem to implicate gynecological factors. It should be noted that during pregnancy the polypeptide hormone relaxin is produced and is believed to be one of the key agents in inducing the laxity of the ligamentous supporting structures of the pelvis which accompanies (and facilitates) childbirth. It is proposed that this ligamentous laxity predisposes those athletic females (who run, kick and pivot) to excessive movement at the symphysis and consequent osteitis.

In consideration of normal joint mobility of the symphysis, Walheim and co workers examined movement of the intact symphysis under traction in cadavers and in volunteers, who were studied at rest in supine position, whilst standing on one leg and whilst walking. During the studies volunteers wore bone mounted electromechanical transducers. The summary of their findings is that all movements of the normal symphysis are less than 2.0 mm. Interestingly, multiparous females revealed greater ranges of movement of the symphysis than nulliparous females, and females generally demonstrated greater flexibility of the joint. Mobility was greatest in the vertical direction, compared with movement in the transverse and sagittal planes and in frontal and sagittal rotation. As a footnote to these findings, Chamberlain in 1930 noted that in a radiological series all patients with symphysis mobility documented at greater than 2.0 mm had complained of pain of the pelvic joints.

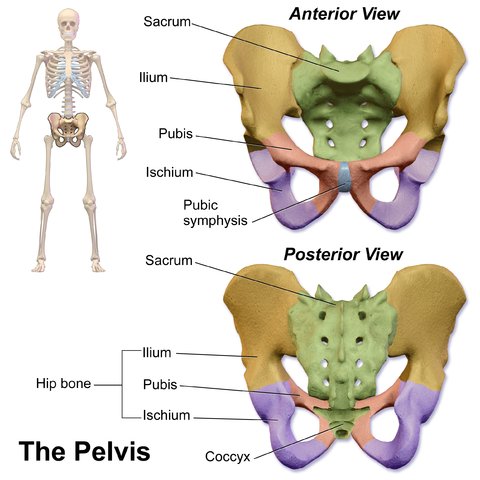

Anatomy and Pathomechanics

The symphysis pubis is a fibrocartilaginous joint between the pubic rami. In addition, the abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis and external and internal oblique muscles) attach distally to the inguinal ligament, conjoined tendon, and pubic symphysis, whereas the adductor muscles (pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis) arise from the superior and inferior rami of the pubis. The obturator and femoral nerves with their cutaneous branches have been suggested as etiologic factors in groin pain. Thus, dysfunctions that affect the pubic symphysis can affect either joint mobility or the musculotendinous attachments of the abdominal or adductor muscles.

Muscle imbalances between the abdominal and hip adductor muscles have been suggested as an etiologic factor in osteitis pubis. Because of their attachments to the thoracic cage proximally and the pubis distally, the abdominal muscles act synergistically with the posterior paravertebral muscles to stabilize the symphysis, allowing single-leg stance while maintaining balance and contributing to the power and precision of the kicking leg. The adductors, because they stabilize the symphysis by bringing the lower extremity closer to the pelvis, are antagonists to the abdominal muscles. In addition, the adductor muscle group transmits mechanical traction forces toward the symphysis pubis during its activity as a prime mover in the soccer push pass, tackling, and directing the soccer ball. Imbalances between abdominal and adductor muscle groups disrupt the equilibrium of forces around the symphysis pubis, predisposing the athlete to a subacute periostitis caused by chronic microtrauma. This microtrauma exceeds the dynamic capacity of tissue for hypertrophic remodeling, resulting in tissue degeneration. Shear stress at the symphysis pubis can also cause sacroiliac dysfunction in osteitis pubis if hip internal rotation is limited in either flexion or extension. This shear stress is transmitted to the symphysis pubis, resulting in either anteroposterior movement of one half of the pelvis in relationship to the other in extension or proximal-distal movement in flexion.

Osteitis Pubis cause can be categorized into two main groups: Overload & biomechanical inefficiencies.

Overload (and training errors)

- Overload (or training errors).

- Exercising on uneven ground.

- Exercising on hard surfaces, like concrete.

- Increasing exercise intensity or duration too quickly.

- Beginning an exercise program after a long lay-off period.

- Exercising in worn out or ill fitting shoes. Go to girdles-and-footwear to read more.

Biomechanical Inefficiencies

- Muscular imbalances;

- Leg length differences.

- Poor running or walking mechanics;

- Faulty foot and body mechanics and gait disturbances.

- Tight, stiff muscles in the hips, groin and buttocks;

It is also associated with urologic procedures and as a complication of various obstetrical and gynaecological procedures including vaginal deliveries. Increased ligamentous laxity or muscle imbalance can act as a mechanism for the development of osteitis pubis in athletes, this acquired laxity maybe a result of adductor and/or gracilis dysfunction and act as a potential mechanism for abnormal symphyseal motion and, hence, for the development of traumatic osteitis pubis. The incidence of osteitis pubis appears to be up to 5 times more prevalent in males than in females.

Osteitis pubis and pregnancy

Damage can occur to the ligaments surrounding and bridging the pubic joint as a result of repetitive stress or by falling, tripping, slipping and also from pelvic surgery and pregnancy. In childbirth it mainly appears post partum caused by a degree of trauma during the birth. Particular movements or activities can cause a slight but continual separation or shearing in the symphysis, which can erode the joint surfaces, causing lesions and a kind of roughening in the area jointing the fibrocartilage and pubic bones that form the symphysis pubis. Symptoms include one or more of the following; pain in the pubic area, hips, lower back and thighs.

X-rays taken during the early stages of osteitis pubis can be misleading, you may feel the pain but the damage doesn't appear on the films, it is only as the process continues that later pictures will show evidence of bony erosion at the ends of the pubic bones.

Stages of pubic symphysitis

Athletes with osteitis pubis were classified into 4 stages based on their presenting clinical diagnostic features.

Stage I includes unilateral symptoms involving the kicking leg and inguinal pain in the adductor muscles. The pain subsides after warm-up but recurs after the training session.

Stage II consists of bilateral symptoms with inguinal pain involving the adductor muscles. The pain increases after the training session.

Stage III comprises bilateral inguinal pain involving the adductor muscles and abdominal symptoms. The athlete complains of pain when kicking the ball, sprinting with rhythm or directional changes, changing positions from sitting to standing, and walking long distances. The athlete is unable to continue sport participation.

Stage IV describes pain in the adductor and abdominal muscles referred to the pelvic girdle and lumbar spine with defecation, sneezing, and walking on uneven terrain. The athlete is unable to perform activities of daily living.

Symptoms of Osteitis Pubis

- The symptoms of osteitis pubis can include: Pain while climbing stairs, running, kicking, changing directions, or even during routine activities such as standing.

- Pain when coughing, or sneezing.

- Loss of flexibility in the groin region.

- A dull aching pain in the groin. In more severe cases a sharp stabbing pain.

- Difficulty in ambulation and the characteristic waddling gait.

- A low grade fever.

- Pain over the pubic symphysis with referred pain into the inguinal region and the groin.

- An audible or palpable click over the symphysis might be detected during daily activities. Muscular imbalances: Tight inner thigh and hamstring muscles and weak abdominal muscles can cause osteitis pubis.

- Leg Length Discrepancy: If one leg is longer than the other, it could contribute to the problem.

Diagnosis

- Blood test.

- Needle biopsy.

- Pelvic X-rays can be normal early on, or there might be slight separation of the pubic bones with patchy sclerosis and irregular cortical margins. X-rays will shows cysts and erosion of the pubic symphysis in advanced cases.

- Bone scan will highlight advanced uptake at the pubis symphysis.

- MRI will show the bone stress injury and swelling present.

- The thoracolumbar junction, commonly refers pain to the groin. Subtle lumbar spine instabilities can cause neural or joint irritation commonly refer pain to this area.

- Associated pathologies, especially adductor or other tendon injuries from recurrent stretching and tearing of the stabilizing anterior ligaments and adductor muscles.

- The whole process usually occurs over a period of six to eight weeks, but symptoms can last as long as six months or more. In severe and long standing cases surgery could be considered.

Management of Osteitis Pubis

Acute treatment starts as quickly as possible after the injury has been incurred. The objective of the acute treatment is primarily to prevent additional injury and reduce bleeding as much as possible. Effective acute treatment will reduce bleeding, formation of scar tissue, the number of complications, which can arise, and the rehabilitation period.Treatment follows the so-called "RICE" principles.

The management of this condition is very much a process of attending to those mechanical factors which appear to contribute to disruption of the fibrocartilaginous joint at the symphysis. As discussed, limitation of hip rotation must first be assessed and, if present, should be actively improved by daily flexibility/stretching exercises. Simple exercises such as sitting with the hip in full flexion and actively stretching the hip joint capsule by pushing the lower limb and hip into internal (and then external) rotation can produce improvements in range of movement over a period of weeks. Sustained stretches are to be encouraged and the caution should be issued that cessation of these exercises can result in loss of the newly gained increases in joint mobility. While there has been no evidence in the literature to support this, it is the author's practice to institute an element of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation into this stretching program as observation has demonstrated that an initial isometric contraction of external rotators of the hip (against manual resistance) followed by a passive stretch into internal rotation often produces immediate gains in range of movement and is therefore a worthwhile endeavor as a 'warm up' exercise prior to any activity. (The same technique is employed of course to enhance external rotation where necessary.)

If there is any associated loss of mobility of the lumbosacral spine, then active exercises should be added to restore normal range of movement, particularly at the lumbosacral junction if affected. There is some debate over the role of sacroiliac joint movement in pelvic bony pathology and, therefore, in rehabilitation but it is wise to correct any sacroiliac joint dysfunction if found. Therapists with skills in this area of assessment are to be employed whenever possible.

Rehabilitation of the musculature supporting the pelvis and hips is a necessary adjunct to management. Hip abductors, adductors, flexors, extensors and rotators, should all be assessed and deficiencies addressed by appropriate daily strengthening exercises. The intent is to support the pelvis in a functional way and minimize excessive shearing/ rotation/ distraction forces across the symphysis during activity.

In case of lack of progress with rehabilitation, a medical treatment can be considered in the form of rheumatic medicine (NSAID) or the injection of corticosteroid around the inflamed tendon fastening or in the pubic bone joint . The injection can advantageously be ultrasound guided. Since the injection of corticosteroid always is part of a long-term rehabilitation of a very serious, chronic injury, it is decisively necessary, that the rehabilitation course stretches over several months to reduce the risk of relapse.

The use of a thermal protective device such as 'Thermoskin' is recommended. A pair of shorts made from an elastic material with a comfortable woven lining appears to produce relief of symptoms by promoting and maintaining local warmth and some compression. Athletes with osteitis pubis often find exercise easier, with less time required to warm up and less discomfort after activity.

Physiotherapy modalities such as interferential therapy, short wave diathermy and other soft tissue 'warming' measures serve to promote recovery by inducing improved local blood flow to the injured area and effecting some local pain relief.

Therapeutic Modalities and Rehabilitation Protocols for Osteitis Pubis

Conservative management of osteitis pubis for all athletes included pharmacologic management consisting of oral ibuprofen, 800 mg 3 times a day for 14 days; daily application of therapeutic modalities (cryomassage, laser, ultrasound, or electric stimulation) for 14 days; and a progressive rehabilitation program.

Ultrasound was not applied to athletes younger than 18 years because of concern for damage to the epiphyseal plates; alternatively, they received electric stimulation treatment.

Electric Stimulation (used in athletes younger than 18 years)

SysStim 207 musle stimulator

Alternating current

Bipolar techniques: active (-) over painful region and dispersive (+) adjacent to the involved adductor muscle group

8-minute treatment

Submotor amplitude

Rate:8 pps

14 daily sessions

Ultrasound (used in athletes older than 18 years)

Continuous wave over pubic bone

5-minute treatment at 1.5 W/cm2, 1 MHz, 10-cm2 effective radiating area.

Cryomassage

10 minutes over painful area.

Ga-As laser

Infrared GaAs pulsed (180-nanosecond) laser (904 nM)

10-W output power

2 minutes per painful spot using grid technique with 2-cm distance between treatment points

4-5 treatment sites total

10 sessions

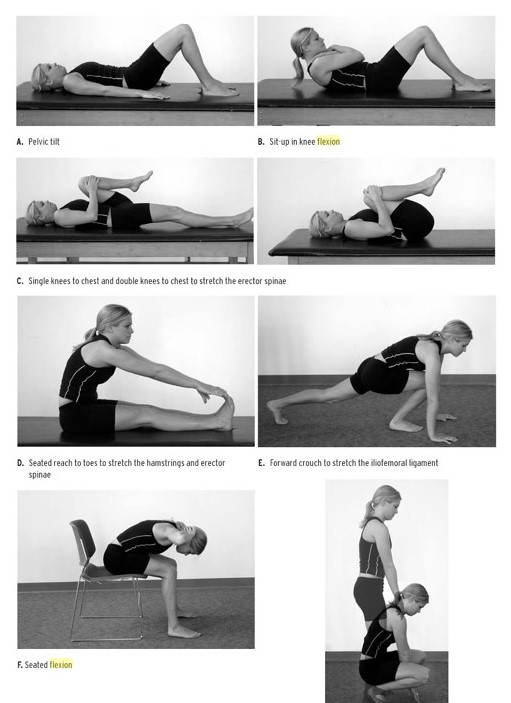

Progressive rehabilitation (exercises added as the athlete progressed through each rehabilitation phase without discomfort)

- Flexibility exercises emphasizing the adductors

- Strengthening exercises of abductor and adductor muscle groups using an elastic band

- Cardiovascular endurance: cycling or swimming

- Walk-jog program progressing to full jogging program

- Exercises on a 50-m incline plane with 10% slope. All exercises performed on the incline, and jogging performed on decline

Line jogging

15-m sprint

Jogging with knee high

Jogging with knee high plus a jump

Jogging with left and right side hops, keeping both feet together

Jogging with buttocks kicks

Carioca: walk and jog

Squat running

Frog leaps - Abdominal exercises

- Progressive kicking exercises short, medium, long distance.

Increasing velocity and kick intensity

Modification of Activity

Read more about Osteitis Pubis on Wikipedia

The difficulty with the management of osteitis pubis in knowing what activity to permit, rather than forbid, because the condition is chronic and many athletes complain that any exercise is painful. Absolute rest on the other hand is usually greeted with horror by the active athlete and the wish to pursue exercise, maintain fitness and avoid the loss of skill(s) generally overrides the notion that rest may be good. Given the understanding of the pathomechanics of osteitis pubis as we know them today, it does seem reasonable to recommend the following: the athlete should understand that kicking, pivoting and running are the main offenders, especially in the presence of stiff or 'tight' hips (manifest particularly by a loss of internal rotation, i.e. less than 45 degree;). Therefore these activities should be restricted until pain, local tenderness and evidence of any inflammation (time to warm up) have largely disappeared. Alternative activities such as (non weightbearing) running in deep water whilst wearing a flotation jacket, cycling (if pain free) and appropriate strength and power training (using the muscle groups about the hips and pelvis in particular) should be recommended as therapy. A more general circuit weights program can be prescribed for general fitness and strength. Swimming is also very useful provided the kicking action does not produce pain. The athlete being treated should be reassured that fitness can be maintained and indeed improved upon with such an alternative exercise program.

As the symptoms and signs of osteitis pubis settle over time, a gradual reintroduction of running, kicking and pivoting can be instituted. Each athlete should undertake each activity as deemed necessary for his or her particular sport over a period of a few minutes initially, followed by gradual increases in the time spent on each activity, the intensity of each activity, and the frequency of each activity all the while being limited by symptoms of pain or discomfort after activity. If pain increases with any activity from session to session, then the period of time, the intensity and perhaps the frequency of sessions should be reduced until symptoms have settled. Then a gradual buildup can be restarted within the limits of pain.This process has no time limits. Some athletes respond over a period of 6 to 8 weeks, whilst others take many months (or even years).

Return to sport is permissible when the athlete can run, kick and pivot (as necessary) with very little or no discomfort, and is actively pursuing a maintenance program for hip flexibility and pelvic and hip muscle strength and power. Relapses are not uncommon and can usually be attributed to premature return to sporting activity or neglect of maintenance programs. Such relapses necessitate a return to the management protocol outlined above.

Return from Osteitis Pubis to Sports physical therapy

Return from Osteitis Pubis to Home Page

Recent Articles

|

Author's Pick

Rating: 4.4 Votes: 252 |