Enhance your health with free online physiotherapy exercise lessons and videos about various disease and health condition

Bicep Tendon Tear

A bicep tendon tear can occur in long head of biceps or distal end of biceps. Here is a comparative study of the two-

Tear of Long Head of Bicep tendonDisease of the long head of the biceps is most frequently a component of the larger spectrum of rotator cuff pathology of the shoulder. In middle-aged patients, biceps tendinosis or frank rupture can occur concomitantly with rotator cuff disease. In the setting of a large rotator cuff tear, the biceps tendon frequently becomes inflamed and hypertrophic and can attritionally rupture, often causing relief of longstanding biceps-generated pain. Isolated rupture of the long head of the biceps should thus be a diagnosis made only after other pathology around the shoulder has been clarified. Isolated ruptured bicep tendon in athletes is rare but can occur secondary to the same traumatic forces that may otherwise cause superior labrum, anterior to posterior (SLAP) tears. |

Tear of Distal Bicep tendonRupture of the distal biceps tendon occurs almost exclusively in males and generally in the age range of 40 to 60 years. It results in 40% loss of elbow flexion and suppination power in untreated pts. Partial bicep tear are typically from chronic degeneration without acute trauma. Prepisposing Factors:

|

Anatomy and Biomechanics of bicep tendon tear

The biceps has a long and short head proximally, which form a bipennate muscle in the arm. It is innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve, which enters the coracobrachialis muscle 3.1 to 8.2 cm distal to the coracoid tip and terminates as the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve of the forearm, which exits from behind the musculotendinous junction of the biceps to supply sensation to the anterior lateral forearm. The biceps tendon attaches to the bicipital tuberosity of the radius, where the bicipitoradial bursa lies between the tendon and bone. The cubital bursa lies above the tendon. The tendon traverses the antecubital fossa, which is bordered by the pronator teres on the medial side and the brachioradialis on the lateral side. The brachial artery and median nerve lie medial to the biceps tendon. The bicipital aponeurosis or lacertus fibrosis blends with the forearm fascia and may or may not be torn in the setting of tendon rupture. The biceps functions primarily as a forearm supinator and secondarily as an elbow flexor.

The long head of the biceps is one of only two intra-articular tendons in the human body (along with the popliteus tendon). It originates from the supraglenoid tubercle and superior glenoid labrum. Three variations of origin have been described: completely labral (50%), labral and supraglenoid tubercle (30%), and supraglenoid tubercle alone (20%). Its function in the shoulder has been debated, but in a younger athletic population, the healthy tendon appears to function as a shoulder depressor and dynamic stabilizer preventing anterior instability.

ClassificationNo commonly used classification exists exclusively for rupture of the long head of the biceps. Habermeyer and Walch’s system for bicep tear in general is useful. Lesions that occur in the rotator interval are divided into the following categories: A, tendinitis; B, isolated ruptures; and C, subluxation. Lesions associated with rotator cuff tears are divided as follows:A, tendinitis; B, dislocation; C, subluxation; and D, rupture. |

ClassificationRamsey Classification of Distal Bicep tendon tear Partial rupture

Complete rupture

|

Clinical Presentation and HistoryMost patients with acute rupture of the long head of the biceps are older and may have had chronic shoulder pain before rupture. Although many patients may recall a sudden tearing or “pop” in the shoulder, pain may not be extreme. In some cases, there may even be a notable improvement in pain after the acute inflammatory phase subsides. Patients with concomitant rotator cuff tears will complain more of overhead weakness, night pain, and pain with shoulder dependency. Physical Examination Examination will typically reveal the classic “Popeye deformity”, but in obese patients with diminished muscle tone, the defect may not be dramatic. Ecchymosis is usually present and may be extensive, involving the entire anterior brachium. Elbow function is generally preserved, but shoulder function may be diminished, and a careful evaluation of rotator cuff integrity is required. Specialized tests for biceps pain include Speed’s, Yergason’s and Ludington’s tests. |

Clinical Presentation and HistoryMost patients are males, frequently muscular, with a history of an eccentric force applied to an arm at 90 degrees of flexion. The patient reports a tearing sensation and sudden onset of pain and loss of flexion and supination strength. Flexion strength usually improves with late presentation, but weakness in supination remains profound. Physical Examination The appearance of the antecubital fossa is marked by moderate swelling and ecchymosis with loss of the normal fullness in the region of the tendon as it crosses the flexion crease. A palpable defect can usually be felt, although the presence of an intact lacertus fibrosis may make the defect less notable. In the acute phases after injury, the patient may have significant loss of active flexion and supination. A partial rupture may have many of the same features as a complete rupture, but generally the tendon can still be palpated in continuity. A biceps squeeze test has been described whereby the elbow is held in 60 to 80 degrees of flexion and the muscle belly squeezed, eliciting supination of the slightly pronated forearm. |

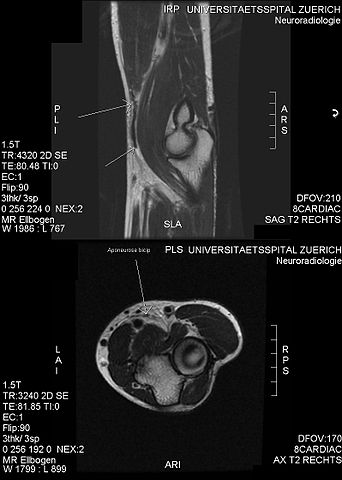

DiagnosisWith isolated tendon rupture, plain films are negative but are suggested because presentation may be quite similar to that of a proximal humerus fracture in an elderly patient. Bicipital groove views may be obtained to characterize osteophytes and evaluate the slope of the medial wall of the intertubercular sulcus (medial wall angle). MRI is indicated whenever rotator cuff pathology is suspected and should be ordered liberally to avoid misdiagnosis of concomitant rotator cuff tears. The absence of the tendon in the proximal bicipital groove is typically found on MRI arthrogram. |

DiagnosisAlthough the diagnosis is usually made on clinical grounds alone, atypical presentations may require further imaging studies such as ultrasound or MRI. MRI is the study of choice for imaging partial tears and evaluating cubital bursitis but cannot always reliably discriminate the severity of partial tears. Plain radiographs are warranted to rule out fracture and assess morphology of the tuberosity. |

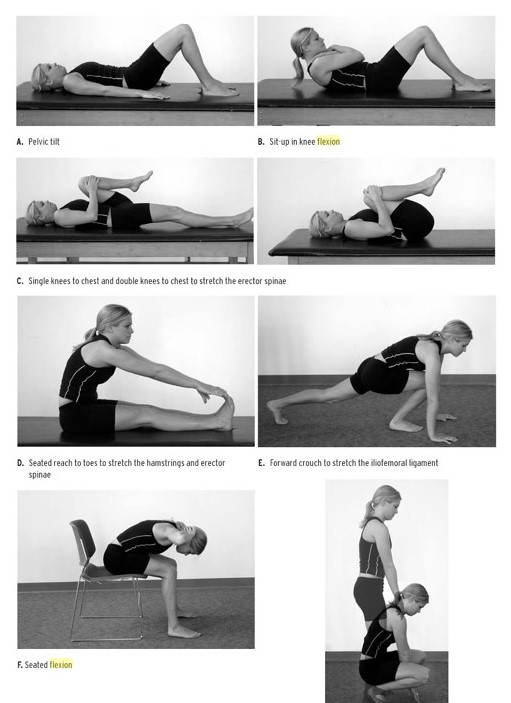

Treatment Options for Long Head of Bicep Tendon TearNonoperative Traditionally, nonoperative treatment of isolated tears of the long head of the biceps ruptures has been recommended for most patients. It is important to counsel patients on the cosmetic sequelae of muscle deformity, but also to emphasize that only minimal loss of flexion and supination strength can be anticipated. Shoulder and elbow passive and active range of motion is initiated immediately, and strengthening can begin in 4 to 5 weeks or when pain resolution permits. Return to unrestricted activities is allowed after 2 to 3 months. Operative Operative treatment of rupture of the long head is often coupled to treatment of concomitant pathology of the rotator cuff. In the setting of open or arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, the rupture of the biceps tendon can be stabilized with open or arthroscopic tenodesis. Biceps tenodesis has traditionally been performed through the deltopectoral interval to visualize the retracted tendon distally in the groove. Multiple techniques exist for tenodesis, including bone tunnels, keyhole technique, suture anchors, and interference screw fixation. Transfer of the long head to the coracoid has also been advocated and may prevent pain at the humeral tenodesis site. |

Treatment Options for Distal Bicep Tendon TearNonoperative A trial of nonoperative treatment is advocated for patients with partial ruptures and elderly or sedentary patients with limited functional goals. Patients who opt for nonoperative treatment should be advised of a loss of 30% flexion strength and 40% supination strength and decrease in supination endurance. Patients are allowed early active-assisted range of motion initiated in the first week after injury. As motion returns to normal, progressive strengthening is advanced as tolerated. Operative As distal biceps rupture becomes a more commonly recognized and treated entity, so have the numerous techniques for operative repair multiplied. The initial reports on repair were performed using an anterior approach and had a high incidence of radial nerve injury. Boyd and Anderson described the double-incision technique with bone tunnels, which had become the standard procedure for many until the introduction of anterior single-incision repairs with improved techniques and implants. Techniques for chronic ruptures range from fixation to the ulna to improve flexion strength only, to recent descriptions of tendon grafting with autogenous semitendinosus, flexor carpi radialis, or allograft Achilles tendon. Partial ruptures that do not respond to conservative treatment are also indicated for surgery with a single- incision posterior approach allowing detachment and re-repair to the tuberosity. |

Postoperative Protocol for Long Head of Bicep Tendon TearWeeks 1-4:

Weeks 5-6

Weeks 7-9

Week 10 Pain-free biceps isometrics Weeks 14-16

|

Postoperative Protocol for Distal Bicep Tendon TearInitial: Posterior splint at 90 degrees, neutral rotation Weeks 1-8: Active-assisted extension and passive flexion allowed with an increase of 10 degrees of extension/wk to full extension by 6 wk. Hinged elbow brace with extension limits Weeks 8-12: Discontinue splint wear, unrestricted motion with emphasis on extension and pronation; progressive resistance allowed Week 12 to month 6: Advanced strengthening and functional restoration Return to play: After 6-7 mo or when strength is 90% of uninvolved side |

|

Postoperative Outcomes for Long Head of Bicep Tendon Tear Outcomes with biceps tenodesis alone have in the past had intermediate results. This is likely due to missed rotator cuff pathology and reinforces the need for attention to additional lesions beyond the biceps. The interference screw technique has similarly had success, with restoration of 90% of strength. The results using any of the accepted techniques are generally excellent. Complications for Long Head of Bicep Tendon Tear Complications of rupture treated operatively or nonoperatively are rare. Heterotopic ossification and fracture after tenodesis have both been reported. A compartment syndrome of the anterior compartment of the brachium has also been noted. |

Postoperative Outcomes for Distal Bicep Tendon Tear Outcomes after chronic repairs are less satisfactory and have a higher incidence of complications. Complications for Distal Bicep Tendon Tear Complications include radial nerve injury, heterotopic ossification, radioulnar synostosis, pain, and loss of rotation, with median nerve entrapment. |

Return from Bicep Tendon Tear to Home Page

Return from Bicep Tendon Tear to Orthopedic Physical Therapy

Recent Articles

|

Author's Pick

Rating: 4.4 Votes: 252 |